Major League Baseball needs to close up a tunnel to their Postseason — the very one I hope my Cleveland Guardians utilize this October.

Over the past few years, the American League Central might as well be known as the "Loophole Division." Play your home games in this particular region of the country and you could conceivably be the AL’s tenth-best club (based on win percentage) and get included in the top six. Worse, the potential exists for a bottom-half team to masquerade as worthy of the playoff bracket's 3 seed — recognized with hosting a Wild Card Series. Undeserving Postseason insertion is bad enough; up to three home games (and a favorable match-up) are a bridge too far.Everything surrounding current Postseason access is the crux of my Guardians frustration du jour. If Tito & Co. can’t take full advantage of the modern rules this year — with a current division leader sitting at 41-42 — then he's not the proper caretaker of the youth movement in Cleveland. It’s the lowest barrier to entry on the game board at present. 87 wins might just hang a banner with the year 2023 on it, done up in Division Winner navy and not Wild Card white. Seems very doable for a club coming off 92 wins and still "ahead of schedule" developmentally; owners of a 2-1 ALDS lead last year with the youngest roster in Major League Baseball.

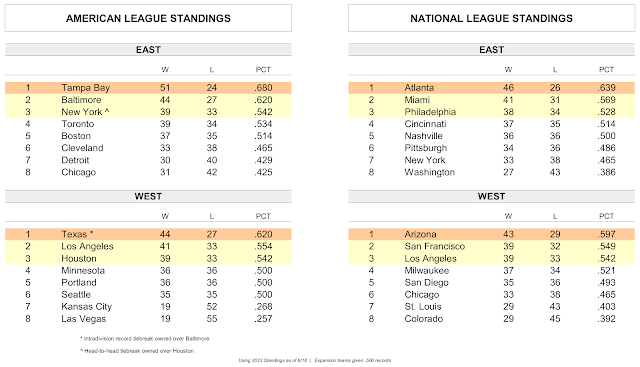

Okay, enough about my personal reasons for therapy and more about Major League Baseball's issues. Each member of the AL Central, including those Twins, would currently fall below the Red Sox for fifth place in the American League East. Framed using this context: The Central's automatic qualifier, comparable to another division's SIXTH PLACE team, would punch a ticket to compete for a World Championship. This is a gift from baseball heaven.

But... it's also one I believe should not last. We're not dealing with March Madness, where the story of a .500 team getting hot in its conference tournament makes for a fun First Four anecdote. This is Major League Baseball and the 119th playing of the Fall Classic. The stakes are a little bit higher here.

For proof the format is creating unfit Postseason candidates, look no further than the National League Central to find [checks notes] the EXACT SAME scenario. One pilgrim alone is a zealot. But two pilgrims together; that's a pilgrimage. Baseball Reference's Detailed Standings of all 30 teams is the perfect visual for these wild times. Names in bold denote division leaders. Look at just how many better records are above those Brewers and Twins:

If the unspoken rationale for a Major League Baseball season being this long is to provide ample runway for the best teams to identify themselves, then the system has routinely failed. And the current playoff format, in just its second year of existence, is on an all-too-familiar path toward snubbery. Someone deserving is going to be left out in the cold; perhaps multiple someones.

Stealing their seat at the table will be at least one "unqualified" franchise, afforded house money to shock the world. After all, a mediocre 13-9 Postseason record (.590 winning percentage) is enough to raise the Commissioner's Trophy — provided the losses do not come in bunches. Tampa Bay almost navigated this minefield to perfection in 2020, the Covid-necessitated precursor to the modern format. The Rays were a pedestrian 11-9 overall that Postseason, but that it was good enough for an AL Pennant and forcing a Game 6 in the World Series.

Point being: Get in and all bets are off; the hot streak necessary isn't as scorching as one might expect. By not being among the 18 clubs eliminated on the final day of the regular season, the harder work has arguably been done. House money kicks in.

And that's the issue. If geographical alignment protects a club that should be watching the playoffs at home, seeing it through to a fluky Championship is no worse than +3000 odds. They've fallen up this far, what's another four weeks?

I have a big problem wrong with this. Because of how short the playoffs really are, I want only the best teams vying for the title.

Let's say a "good but not great" NFL team hits the 10-win plateau in the new 17-game schedule. Undoubtedly not earning a bye, they would need to produce 40% of their regular-season win total — without a single loss mixed in — to lift the Lombardi Trophy. An NBA team of comparable middle-of-the-standings resume amasses ~45 wins on an annual basis. The 2022-23 Miami Heat team, which appeared in the Finals as an 8 seed, only got to 44. With four rounds of four wins, their playoff run required a 36.3% reprise of what was accomplished from October-April.

The World Champion Denver Nuggets posted a formidable 53 victories in the regular season and got their 16 (30.2%) in the playoffs. Similarly great baseball teams have to do a third of that work. It's really the only way to explain the success of teams like the 2000 Yankees, 2006 & 2011 Cardinals, 2014 Giants, and 2021 Braves. Each won it all despite having 90 or fewer regular-season wins. Arguably, the entire 21st century has been more flukes than #1 overall seeds.

It's due to the fact that the sport is overly front-loaded: Six months to thin the herd and only play one more.

87 regular season wins in any other sport is literally impossible. It's more than the 2023 Eastern Conference Champions (Miami Heat and Florida Panthers) combined. But such a season falls into the "good but not great" category for Major League Baseball. In a vacuum, the quantity and frequency of winning that much/often is commendable. In this year's loaded American League East, it might not be good enough for third place.

Should a playoff team sneak in with 87 wins, they only need to come up with 14.9% of their regular-season win total during the playoffs. Win 105 ballgames and bypass the Wild Card round? You only have to "prove it" by recreating 10.4% of the completed work featured in the portfolio.

This could all change in an instant, however. The year that MLB ultimately expands to 32 clubs is the year that this mess of a bracket could start to make sense; start to require a larger percentage of the regular season's elite play be matched.

-----------------------------------

Options For When Baseball Grows to 32 Clubs

The days of three divisions in both the American and National League are clearly numbered. Major League Baseball expansion is coming during Rob Manfred's time as commissioner. And, in that, everyone with a basic understanding of arithmetic knows clubs will be grouped into either twos, fours, or eights. Three and six ain't going into 32 evenly.

The solution is sitting on the table, but it isn't a guarantee that league executives don't muck it up by tweaking too many variables in the equation. Should "the smartest guys in the room" decide to abandon all AL/NL ways of life — now that the designated hitter and persistent Interleague Play are universal — they will lose this fan for good. I'm clearly receptive to a little change, but not prepared to get the bends.

I don't truly remember the Brewers ever being in the American League, but I definitely recall the Astros playing in the NL. A one-off League swap like that was unsettling enough for my OCD desires of stability/continuity. Transitioning the affiliation of a dozen is an inflection point in baseball's timeline that would literally kill me. With a rare exception (perhaps a Colorado to the AL), the sanctity of the American League and National League must survive this next wave of expansion.

I've already had to [begrudgingly] give up what I call my favorite team since 1993. 12 year-old me: The Indians play at Jacobs Field. 36 year-old me: The Guardians play at Progressive Field. Somehow, I'm supposed to pretend both of those statements have always said the same thing. Reconditioning my brain to embrace this was plenty; "up" is already "down" in enough ways. For several close friends, these semantic adjustments were enough to make them divest all MLB passion.

Launching a model where a Cleveland, Toronto, Detroit, Philadelphia, Boston, and both New York teams are now one geographically-linked hodgepodge bastardizes the very framework of this game's great past. It might make logistical sense, but that will be the day I'm officially comfortable no longer following along. That's much more than a name change; it's Etch-A-Sketch-ing everything drawn heretofore and starting over. I don't feel I'd be alone in using that as the moment for a clean break.

Adopting an (8) four-team division format, like the National Football League, hits a few roadblocks for me. Namely, run the simulation of a regular-season breakdown in opponents. We're either going to get 14(!) games against our team's three division rivals each season or everyone in this industry is going to have to get used to the five-game series being the norm.

Showing my math on this: (14 x 3) Division + (6 x 12) Remainder of the League + (3 x 16) Interleague = 162. I hate that. It's one more intradivisional match-up than we currently have, but worse, because there would now be two new franchises in the ecosystem that we all would want to see. The quantity should be going down not up.

As a Cleveland diehard, I don't want to see the Chicago White Sox 14 times a year and the new Portland franchise thrice. This also makes me begin to question the quality of any division winner that feasts at the endless buffet of empty calories. Have the worst team in baseball in your "pod" and theoretically a 10-4 record is laying at your feet; 10% of the way to a 100-win season off one opponent.

Dropping the in-division meetings to 10 occurrences per year (7 vs. Rest of the League, 3 vs. Interleague Opponents) means you're likely staring down the barrel of (2) five-game series vs. your geographical partners. I cringe a little at this. And the cause can be found with the frequency. Disregard the overall quantity for a second, teams jockeying for position in the AL East standings need to see the name of the others — equally vying for the divisional top spot — show up on the calendar more than twice a season. Period.

Now, I'm fully aware Minor League Baseball has transitioned into the land of the six-game series. People that work at these ballparks love it. Players enjoy the consistent Monday off. Executives sure love the "week here, week there" rhythm to it. Owners can't be upset with how much it is helping with travel expenses. However, this is Major League Baseball. I'm not saying we frivolously light piles of money on fire; there is undeniably money to be saved in logistics, scheduling, flights, accommodations, etc. But, again, this is also Major League Baseball, valued at a record-high $11.9 billion. We shouldn't turn it into EconoMode overnight at the detriment of the variety a typical schedule can provide. There's beauty in the randomness. Becoming overly formulaic/monotonous might be too much medicine for the few minor symptoms that ail.

It's not like the six-game series is devoid of drawbacks. Animosity and tensions can run extra high (player vs. player, player vs. umpire, manager vs. umpire, manager vs. manager) when you're spending a full week with the same cantankerous people. Furthermore, the business of sport, particularly at the gate, relies on a freshness/uniqueness of visiting superstars, and a sense of "one night only." Baseball already struggles with the "If I miss it tonight, there's always tomorrow" mentality — in a way that its North American pro sports peers do not. Why should MLB add fuel to this fire of apathy?

-----------------------------------

Addressing 162 (And The Best-Of-Five Division Series) While We're At It

There's also the issue of rest/rust in which the five-game Division Series turns a bye into an unwanted reward. The risk is high of running into a buzzsaw with the margin for error limited to two slip-ups. A third clunker can end an incredible season before it ever really begins. I certainly had my speculations going into the 2022 Postseason. And the predictions turned out to be spot on, as the National League's #1 (Los Angeles) and #2 (Atlanta) both lost their first match-ups.

This round has to morph into a best-of-seven, to let the cream rise to the top. If nothing else, the bye should earn these teams an extra loss to play around with. With eight days between games (final regular-season game on October 2, ALDS/NLDS Game 1 on October 11) they deserve a chance to get their feet back underneath them.

Some leagues view playoff duration as a point of pride. It is a grind that always crowns the most-deserving champion. The NHL not only embraces its "Second Season" nickname, but markets it as such. While the playoff quantity never truly comes close to a second full helping of 82 games, teams could end up playing a schedule that is 34.2% the length of the regular season. With a new play-in game for the NBA, an 8 seed could end up playing 30 games after their traditional 82. That is an insane 36.6%. Baseball is a relative sprint by comparison; a maximum of 13.6% for those that require the Wild Card Series. Is the answer more playoff baseball games? The fan appetite and weather don't seem to suggest "yes."

This isn't to say that the general public finds Postseason baseball games less exciting than playoff NHL match-ups. More of the former is definitely welcomed by all; October baseball is high drama and fun to be a part of. The key difference between sports is in total quantity of games from Opening Day to trophy presentation. Even with four full rounds — and a maximum of 28 additional games — the NHL's potential total can only ever get to 110. Baseball's 162 plus 21-23 (depending on bye status) teeters on excessive. No one is here for watching/playing 185 games a year. Perhaps it is the regular-season quantity that needs the change.

-----------------------------------

Next Comes The Question: How Many Teams Get Into That Playoff?

Four division winners and two Wild Cards? Same critique I had of that exact setup in the NFL from 1990 to 2020: If the ideology is 1) Byes are a good/valuable commodity (debatable, but most sport executives seem to think they are), and 2) Winning a division is a reward that creates a protective class, then how come two of your teams that satisfy the assignment don't get the same prize? It's a circular reasoning fallacy where these clubs cannot drop to the five or six seed, but also don't reap the same benefits of a one or two. What in the world are they, then?

And you might come back with "Well, [Insert Team Name] didn't have as good of a record as the top two division winners." To me, that's too subjective. Were the schedules equivalent enough — in terms of who, when, and where common opponents were played — to unequivocally determine superiority? The lesser-quality team checked the same box as the others. The preseason goals were met just the same.

I say that if you want to provide two byes per league, that's fine. Not my thing, but it's your prerogative. My simple follow-up is always going to be a staunch belief that the ratio of division winners and those receiving a bypass to the second round must be 1:1. The answer is right there in the question: "How many byes on this half of the bracket?" Two. "Okay, so how many are division winners?" Two.

Like many of the best football (soccer) tactics over the years, you sometimes have to go backwards to go forward. In this context, it means a pre-1994 look to the MLB standings, but with the same playoff entry mechanisms of today. My proposed realignment looks like this:

Playoff expansion should not come with any league expansion. I'll scream it until the day I die: An eight-team bracket in both the American and National Leagues would take too long, negate the need for any regular-season game quantity beyond 150, and also water down the exclusivity of Postseason qualification. Keep it simple, stupid. Six participants per league, two byes, and two best-of-three "play-in" series need to be locked in as the constants.

The craziness surrounding 2020's Covid year gave us a glimpse at what a 16-team MLB bracket could look like full-time. And, while I understood the competitive balance need for it — in an abbreviated 60-game regular season — I never want to see the likes of it again. This wasn't professional baseball:

The whole ordeal ran from September 29 to October 27, and that was with a best-of-three, best-of-five first two rounds. Expand that, slap it on the heels of a 162-game schedule, and even a Big League junkie like me would be saying "No Más!"

I'm here for Cinderella showing up in certain sports, but baseball has a unique limit on parity, in terms of fan appetite. The explanation is quite simple: What's the point of playing 27 days a month from April-September if an 8 seed can knock you out in two days? There's no tolerance for a mini losing skid.

Worse, the 2020 Brewers were 29-31 and made it in, suggesting sub-.500 clubs would show up for Postseason play on an annual basis. Leave that nonsense for the small sample size of the NFL.

Allowing half the field to make The Dance isn't baseball's M.O., either. That's the NBA and NHL's schtick. Both leagues opened the floodgates to 16 participants in the '80s. Slowly but surely, expansion has brought down the percentage of those that do make it versus those that don't, but not to a point where any casual fan overly cares about the regular season. "Wake me up when we're in."

Now, with completed expansion, hockey is finally back down to 50% inclusion (16 out of 32). Much better than the 76.2% (16 of 21) first introduced in 1980, but still not my ideal. Fundamentally, a regular season doesn't accomplish anything if a majority advance.

In recent years, basketball has gone the opposite direction. With a new play-in tournament, 20 out of 30 NBA teams qualify for some form of the postseason bracket. Giving two-thirds of the league a chance at a title is a monstrosity.

Remember, we're talking about baseball. The 1968 pennant winners — Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Cardinals — didn't receive a hat and t-shirt for winning a Wild Card Series; didn't strap on the ski goggles and soak the clubhouse in champagne and beer. They just went directly to the World Series. Ho hum. That was only 55 years ago. A life without any playoffs in Major League Baseball is not exactly ancient history.

Hell, the first Division Series didn't take place until 1995. Suddenly, we're talking about adding a full round in advance of that — in which no one gets a division-winning exemption? That's gonna be a "no" from me, dawg. Growing the playoffs from ostensible nothingness to 16 participants, inside of two generations, is a pendulum swing too extreme.

The Goldilocks Principle asserts people of my father's age are equally wrong in the opposite way. Having no playoffs wasn't pinnacle baseball either. True, the objective was clearly understood by all parties on Opening Day: Finish atop the AL or NL and you earned that World Series berth. But old timers yearn for a return to this way of life because of selective memory. It's easy to look upon the format fondly in the glow of Championship years, when playing for a trophy meant there was no multi-round gauntlet to endure. What happens to that logic when the local ball club is 9.0 games back by the end of May? How quickly we expunge those occurrences from the mind. With only one way in, that is a real possibility.

Thus, I'm proposing we turn back the clock, but not thaaaaat far.

Impartially, many things have changed for the better since 1968. The Wild Cards are a beautiful blend old-school and new. They keep more teams in the hunt, deeper into the year — making a better on-field product. Teams like the 2023 Seattle Mariners aren't on life support, 8.5 games behind the West-leading Texas. Flip over to the Wild Card Standings tab and the GB shrinks to 3.0.

This arrangement feels so organic to me. The fundamental building blocks to the plan have been living (albeit dormant) inside the sport all along. It is a Base Eight league; always has been. For 59 seasons of Major League Baseball, a fan/player/manager/owner could open up the newspaper to find their ballclub sitting in 8th place... and be none too pleased about it. And it may sound strange or sadistic to want to see this scenario make a comeback, but the context around cellar dwelling has changed.

Unlike your grandaddy's eighth place, however, the White Sox wouldn't have to catch the 51-24 Rays. They'd have the "modern luxury" of needing only to run faster than the slowest — Houston's 39-33. After all, hope is a powerful economic driver. A last-place club potentially buying at the Deadline? What are world.

The glowing example of how my proposal rights wrongs can be found in the San Francisco Giants from 1993. That club won 103 games, but did not qualify for the NLCS that year — still the only round of the playoffs at that time. It could be argued that denying the second-best team in all of baseball a spot in the playoffs played a role in everything that transpired over the 18 months that followed. This list includes the establishment of the Wild Card and six divisions, labor unrest over a salary cap and revenue sharing, and a vacant commissioner's chair.

-----------------------------------

It's reminiscent of Gary Gulman's state abbreviations bit. The task starts off so promising that it seems like it'll be buttoned up in five minutes. Working your way down the Atlantic coast, the AL East would consist of Boston, New York, Baltimore, and Tampa Bay. Done. Easy. Even if Tampa Bay has to leave town for Montreal or North Carolina, the geographic cluster would remain the same.

Similarly circling teams in the Pacific Time Zone, your AL West would be Seattle, expansion Portland (or Salt Lake City), Las Vegas, and Los Angeles. Neat and tidy. Next.

Clubs around the Great Lakes, east to west... Toronto, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago. Ope. What do you do with Minnesota? Which of those clear-cut Northerners are you throwing in the South with Kansas City, Texas, and Houston? This feels like a non-starter; all five cities are above the 41st parallel. So do you end up having to switch some NL teams to the AL? I don't know if the buy-in is there, as it would take more than one club to say "yes."

The same problems occur in the National League. An East with New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and Miami (straight down I-95) is nearly identical to its American League counterpart. It works too well to not press on, right? The trouble is you run into all sorts of ways to conveniently cluster NL teams in threes and fives, but not fours.

San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, Arizona, and Colorado — our contemporary NL West — are so isolated that dropping one is illogical; exacerbating an island effect. Colorado ain't exactly "North." Furthermore, Pittsburgh and Colorado being division mates would create one hell of a competitive/travel distance imbalance. Toss the Rockies in the NL South and you turn your back on a delightful 300-mile-radius circle you could draw around expansion Nashville that encompasses Cincinnati, Atlanta, and St. Louis.

The solution is so much easier. American League cities west of the Mississippi [River] are West; east are East. The same is true-ish of the National League, with the exception of Milwaukee and Chicago. North America's longest river has conveniently split our country down the "middle" for centuries. It can continue to do so in the AL; that little plastic grocery store checkout divider just needs nudged over to Lake Michigan for the NL.

-----------------------------------

Analyzing The Future System Using Today's Data

The standings as of June 18, 2023 are impeccable at depicting my point. I literally could not ask for a better real-world example to show the differences between the current format and my proposed.

Huge caveat: The records will undoubtedly change come September. We're not likely to see preseason contenders such as the Mets, Mariners, Padres, and Guardians stay buried in the middle of the pack all Summer. Similarly, there's a chance the Twins and Brewers start to pull away and make the records of the Central Division Champions respectable.

The following is the crapola that would be bestowed upon baseball fans, if the season ended tonight. Ya know, after the city of New York hosted ESPN's Sunday Night Baseball for what felt like the 19th time this season:

Change the names on the seed lines, but the exact same scenario is playing out in the National League.

As punishment for underachieving, the 6-seed Los Angeles Dodgers would get to beat up on the Milwaukee Brewers — while their division rival San Francisco Giants would have to fly to Miami to take on a gritty, up-and-coming Marlins squad. How does that make any sense? The better finisher in the NL West would draw the tougher out. Conceivably, the Giants could tank the last few games of the regular season to back into that sixth spot. Strike three. Laugh and dismiss, but it's a plausible strategy; one that shouldn't have to ever be entertained.

Part of the reason San Francisco would even consider it is because they, like the Angels in the AL, would be forced to travel when they shouldn't have to. So, if you're already destined to play a Wild Card Series on the road — with a ceiling that is the 5 seed — why wouldn't you play the match-ups and seek out the 6?

My proposal also allows the Phillies to sneak in and provides a glimmer of hope for repeat magic to their 6-seed World Series appearance last year. Having both of last year's pennant winners watching from the couch isn't right. Sure, they could be playing better baseball. But they're definitely playing better than Minnesota and Milwaukee.

-----------------------------------

The Future of Major League Baseball Visualized

In a previous piece, I outlined how a Nashville MLB franchise (that feels inevitable) must belong with the National League. A simple map bears this out. Tennessee doesn't do anything to the American League's geography, other than keep Seattle on an island, and firmly place an expansion team on a new one.

Nashville in the AL would also make the NL break up a pair like the Brewers and Cubs (for a second time in their histories), which doesn't make an overwhelming amount of sense. Coaching 101: Don't make moves just to make moves.

Relocating Tampa Bay is not something I want to do. But it becomes really enticing when you look at my AL East map. It's already so northern; Montreal would do so well in that cluster. Even a Southern city like Charlotte or Raleigh would bring its "center of mass" up 500+ miles.

-----------------------------------

Final Thoughts For Your Thoughts

Admittedly, the September standings won't look much like they do mid-June. However, seeing all five teams from the AL East do what they've done so far perfectly illustrates some hypothetical possibilities that the contemporary structure would be ill-equipped to handle. In other words, the wrong teams would be included and much of the seeding would be incorrect — undermining the whole purpose of the regular season.

In short: A three-division format will always be broken if one isn't treated the same as the others. Having more division winners than byes works for the NFL, because it's not just a singular odd duck per conference.

I'd be the first to admit the 2022 Cleveland Guardians didn't do enough in the regular season to earn a home series against Tampa Bay. They were the fifth-best win percentage team in the American League. Their geographic alignment earned them protection. Which begs the question: Why are we treating some division winners differently? We're half in and half out. Either rank it 1-6 solely on merit or eliminate all rewards for sitting atop a column in the standings after Game 162. This in-between is asinine. And the ripple effect runs all the way down the bracket. Every match-up dynamic changes because of it.

If you get down to brass tacks in regards to the intention of subdividing into (2) three-division Leagues, it was solely to protect owners. Smaller groups keep more teams closer to the top for longer. It was nothing more than a raise of the net below the trapeze; franchises couldn't fall too far out of contact with the leaders. More buyers at the Trade Deadline. More "We're still in this race!" More butts in seats around the time kids go back to school.

But then in the last two years, the expanded quantity of Wild Cards doled out rendered this ideology moot. Who needs the floor to raise if you have three additional Postseason spots that could care less what division you come from? Last place is no longer a death march. Real world example: There's not a single Boston fan paying any attention to the GB column (which stands at 14.5) in the AL East. With the Rays playing .700 ball, the only thing that matters from now until October 1 is the horizontal line separating sixth from seventh in the Wild Card standings. It's the cut line in a golf tournament. Unless you're playing them directly, Tampa Bay's record means nothing to you.

Scoreboard watching would transition from games containing geographic rivals to those in places like Houston and Los Angeles. That doesn't seem totally right, either. So why not blend a little bit of the regionality back to this contemporary open access (i.e. college football independent status) to the playoffs?

That's the modern concept we'll keep. We'll now graft it off and stitch it up to the old ways. The current format has never worked quite right. But I believe it was simply ahead of its time. It needed the right divisional breakdown for it to really show off its capabilities.

Go back to two divisions with byes the reward for winning. There would be fewer occurrences of a second-place team finishing above everyone else in the league. That, or seed every single playoff team on overall record and be done with it. Beginning two years ago, the NBA rescinded a vow it used to make to division winners — no longer guaranteeing them seeds 1-3 in each conference. The Utah Jazz, winners of the Northwest Division in May, were the West's 5 seed.

It doesn't take much to see how vital it is for current commissioner Rob Manfred to finally get this rectified. It's a sport that is a marathon until the very last mile, where it stylistically shifts to a sprint. Everything managers preach during the Dog Days of Summer is thrown out the window in October. Have your favorite team catch fire at the right time and you could watch them the Commissioner's Trophy and attend the parade. We'll never know who would have won some of those mid-'90s titles if the system provided proper order. Here's to hoping my children never have to speculate in this same way. All the logistics, right down the Minor League ladder, are already sorted: